Yesterday

During the WWII, Sinti and Rroma fought against the deprivation of their rights and their “racial” registration from the very beginning. They protested against discriminatory regulations and attempted to obtain the release of deported family members through petitions or personal intervention. They worked closely together with resistance groups in the occupied territories. They played an important role in the national liberation movements, especially in eastern and southeastern Europe, and they also cooperated closely with the Résistance movement in France. A large number of Sinti and Roma lost their lives in the armed struggle against National Socialism. Sinti and Roma also offered various forms of resistance in the concentration camps. A highlight was the revolt in camp section B II e of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the “gypsy camp”.

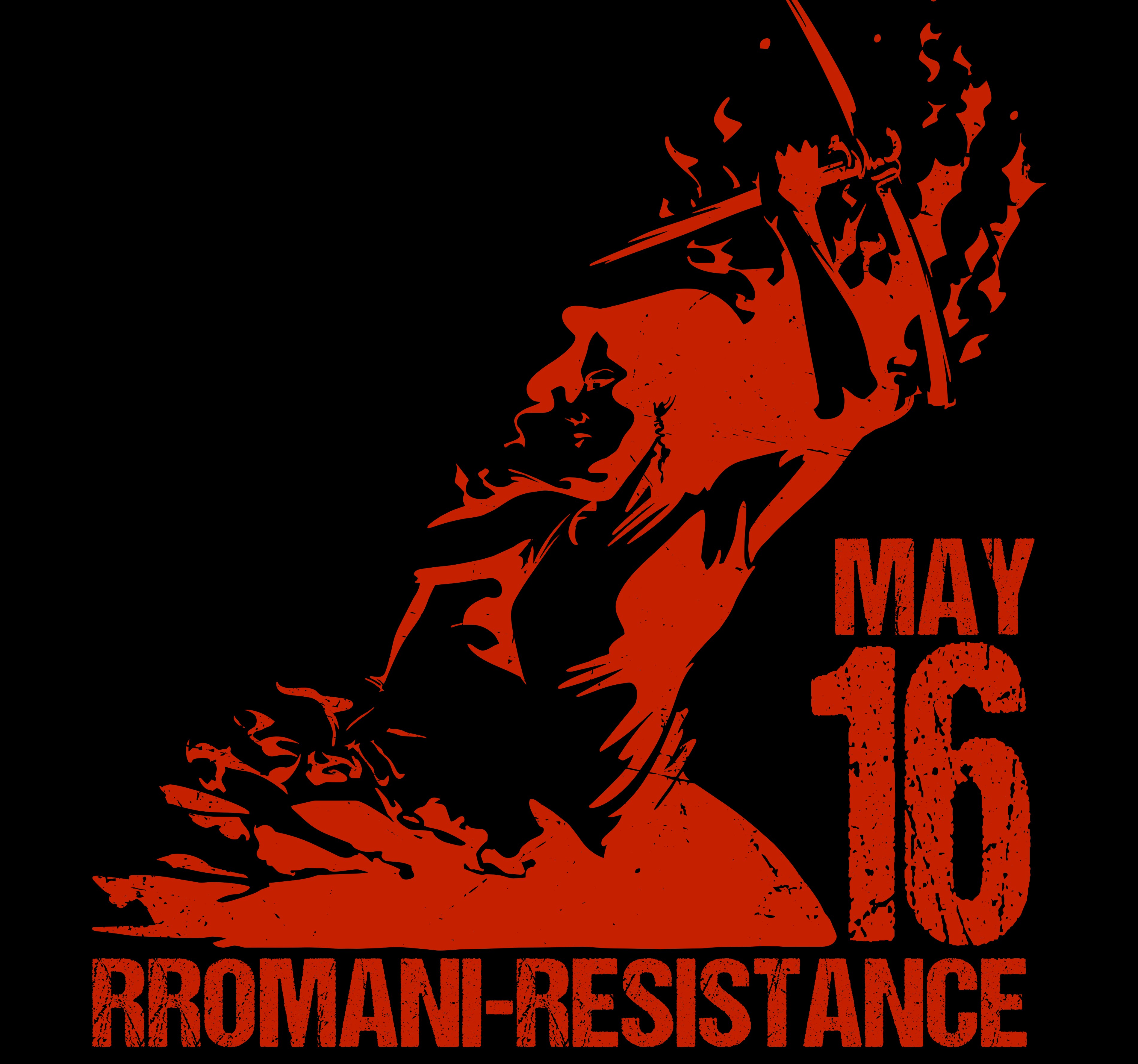

On May 16, 1944 men and women of the Auschwitz II Birkenau “Gypsy families’ camp” warned by the internal Resistance Network of the camp, organized in order to fight off SS guards who came the same night to lead them to the gas chambers. The leaders of this insurrection (one of only two known insurrections, with the almost simultaneous revolt of the “Sonderkommandos”) were scattered to be killed on other sites of the Third Reich. Men, women and children that remained in the “Gypsy families’ camp” were exterminated in the end, starting on the eve of August 2, 1944 and continuing through the night to the next day. The internal Resistance netwotk of the camp (gathering jewish prisonners, polish prisoners, and inteligence etc..) finally uprised on October 7th 1944.

Today

The history of the Roma Genocide has not reached yet a proper recognition by States and Institutions in Europe and the world. Commemoration ceremonies are often misused by institutions. In designating the people primarily concerned by a commemoration to appear exclusively as victims, they achieve an objective of “repentance of the executioner.” In doing so, they are essentializing the figure of the victim and justifying the figure of the institution as a “moral shield” placed between the victim and the “perpetrator.” Paradoxically in this situation the “perpetrator” is the institution that still remains in control and often practices the same mechanism of exclusion of the Roma using the antigypsyism rhetoric. The given ceremony is thus formalized under the exclusive management of institutions, and those people who are primarily concerned appear only as representations of victimhood addressed by these same institutions. The Romani Resistance initiative proposes an alternative methodology that consists of formalizing collective memory under the direction of those who are primarily concerned, so that they can decide on the appropriate form of memory including the usage of any symbolism in any commemoration. With an objective of bettering the everyday participation in democratic living by involving the “demos” in democracy, by involving the common citizens from which a civil society draws its authority and its responsibility, we are reappropriating our history.

It is extremely relevant, on the contrary, to associate the commemoration of the destruction process, with the description of its unique complexity in a celebration of heroism. This exemplary act of resistance is teeming with courage and dignity. This act has also unfairly been kept in the silence of history till now. Is it because it speaks to young citizens, Rromani and non-Rromani alike, facing uncertainties in the current climate of Europe and its commemoration carries implicit promises that have remained unfulfilled to this day ?

Commemoration ceremonies are most often organized by institutions. In designating the people primarily concerned by a commemoration to appear exclusively as victims, they achieve an objective of “repentance of the executioner.” In doing so, they are essentializing the figure of the victim and justifying the figure of the institution as a “moral shield” placed between the victim and the “executioner.” Paradoxically in this situation the “executioner” is the institution that still remains in control. The given ceremony is thus formalized under the exclusive management of institutions, and those people who are primarily concerned appear only as representations of victimhood addressed by these same institutions. The Romani Resistance initiative proposes an alternative methodology that consists of formalizing collective memory under the direction of those who are primarily concerned, so that they can decide on the appropriate form of memory including the usage of any symbolism in any commemoration. With an objective of bettering the everyday participation in democratic living by involving the “demos” in democracy, by involving the common citizens from which a civil society draws its authority and its responsibility, we are reappropriating our history.

Rromani Resistance is most inclusive at every level. If we say the “Genocide of the Gypsies” within the strictest privacy of family relations ravaged a limited group of people (albeit a diverse group including Manouches, Sinté, Roma and various itinerant peoples), we can say on the contrary however, it is Resistance that has always resulted in the making of partisan friendships, bringing together women and men who in addition to belonging to this community of friends, had various individual affiliations. Thus, the network of internal resistance in Birkenau to which the Roma and Sinté leaders of May 16 belonged, also counted Jewish peoples of different nationalities, , and others. Resistance against the present and future political crimes of the State cannot be acted upon by a prince, or any such privileged position of temporal power, but only by the common citizen. Giving back the power contained in the revolt of May 16, 1944 to those primarily concerned, is to give them the tool to reform the multiplicity of friends that should be working together as a “demos”: a community of resistance fighters.